In the fall of 2011, I was living and freelancing remotely in Tel Aviv, which is a major metropolis along the Mediterranean coast of Israel—vibe-wise, it’s somewhere between Manhattan and Miami. My good friend Idan had promised to take me to Hebron, a city in the West Bank controlled jointly by the Palestinian Authority and the Israeli government. He had been stationed there for a while during his time in the IDF (Israeli Defense Force, the military service which is mandatory for young Israeli men and women) and had been meaning to take another visit, especially because of the significance of the city to the Jewish religion—Hebron contains the tomb of the Matriarchs and Patriarchs: Sarah, Abraham, Isaac, Rebecca, Jacob and Leah.

Photos by Alyssa Kurtzman

I was intrigued to see such a significant (albeit difficult to get to) spot, especially with Idan, who is a veritable encyclopedia of Jewish lore and, even though it’s not his first language, probably speaks better English than I do. While in the IDF, Idan had been a pretty big-deal military paratrooper but sadly can’t disclose most of his airplane-leaping past. A slight guy, he has a seeing-eye-school flunkout Golden Lab named Ray (irony intended), and his drinking stories usually end with “and then I beat the shit out of him!” We made plans to go to Hebron in November, a few days before I was scheduled to fly back to New York. Needless to say, I decided against telling my parents in advance that we were taking a jaunt into Palestine.

Let’s pause and take note that everyone and their urologist has an opinion about Palestine. It’s a polarizing topic, and I expected to find it just as tumultuous a place. The furthest I had previously been into the West Bank was a couple months earlier, when my friends and I had raced up the Mount of Olives in Jerusalem for kicks and, needing a place to buy water, wandered into East Jerusalem (which was totally uneventful). I was very curious to see what deeper parts of the West Bank would be like, particularly in a city both so theologically important and so marked by conflict. Control of Hebron has changed hands and seen violence many, many times since Israel’s independence in 1948. Currently, a tense peace is maintained in Hebron by the fact that both peoples manage to get around without almost ever seeing each other.

The day came for our field trip to Hebron. Idan and I hopped an early coach to Jerusalem, where we switched to a second bus with reinforced, bulletproof windows heading into the Territories. It had occurred to me earlier that I might need a passport, but Idan kind of rolled his eyes at me when I brought it up and ensured me that there was no sort of “border” process. Much of the highway we passed through, as we wound our way eastward over some mountains, had cement curved walls extending from the cliffs above, apparently to prevent kids from hurling rocks down onto passing vehicles. Adventures!

After an hour or so, the bus stopped in Kiryat Arba, a Jewish town bordering Hebron, and the bus driver made an announcement. Hebrew is not a strength of mine (let alone muffled Hebrew) so Idan translated: the bus wasn’t going any further. Why? Who knows. “Okay, no problem,” said Idan. “We can hitchhike the rest of the way.”

I guess if you’re going to hitchhike for the first time, Palestine is as good a place as any.

We waited at a main road between the two towns until a woman in a small car pulled over and rolled down her window. Idan told her we were going to Hebron, and she said to hop in—she was headed into the city center to set up for a friend’s wedding. We wedged ourselves into the car, which was stuffed with streamers and balloons, and she streaked off up the windy road around another steep hill. She let us off near the entrance to Hebron, which was surprisingly desolate for a Sunday (a weekday in most Middle Eastern countries). We headed toward the giant, ancient tomb, observing some of the homes along the way.

Photos by Alyssa Kurtzman

Jews and Arabs in Hebron live quite literally on top of each other. Some of the buildings along the border of the two communities are owned by differing families, one (Jewish) entering through a door from one road and taking the bottom floors, and another (Arabic) entering through a door from a road on the other side, and residing in the upper floors. Two different tenants, living in one building, never seeing each other. This isn’t to say that these two families would lunge at each other with kitchen knives if ever they met, but it does point to the kind of tacit truce that exists between their communities, each claiming their right to such an important religious focal point but trying hard to avoid an excuse to engage in any more violence. Interestingly, many of the homes have locked screens completely covering the terraces, not to keep the people inside safe, but to keep them from throwing rocks or bottles onto the street below.

On our walk over, I began to hear what sounded like speakers switching on all around us. I can’t say that I wasn’t a little on edge by this sudden, 360-degree sound, but Idan recognized it immediately as one of the five daily Muslim prayer calls. At once, dozens of loudspeakers all around us began booming out the ululating pre-taped prayer chant from every mosque in the city.

Standing in the shadow of one of the most important relics in monotheism, hearing these ghostly echoes bouncing off the hills around you—this is a point at which you become keenly aware that you are in the middle of a place that is vital enough to have sparked wars, both on the ground and in the chambers of the United Nations. The vibration of the panoramic sound is absolutely unreal—it’s like being swallowed up by religious purpose, like the ground under your feet is the nucleus of ideological gravity.

I’m getting carried away here. Trust that it was a sound I’ll never forget—especially because I managed to record it the next time it happened that day. You can listen to the recording here and I recommend you give it a listen, because, whoa.

The prayer ended, the world stopped vibrating, and we proceeded to go find cigarettes for Idan. Waiting for him, I hung out at a gift shop next to the tomb, where there were plenty of tchotchkes for visitors of any of the three major monotheistic religions. We then walked up the long ramp to the entrance, which is about halfway up the massive structure. A young, bored-looking guard waved us in, which was pretty illustrative of the trip so far—simpler than I had ever imagined.

A classroom inside the huge building’s entrance was filled with fidgeting young boys studying Talmud. Idan went to grab a yarmulke (the round Jewish prayer cap) as I looked around. There’s something really exciting and unnerving about visiting a place that’s extraordinarily important to your culture and that almost none of your ancestors have probably ever seen in person.

We followed some signs to a large chamber, where individual gated mausoleums marked each burial spot with a banner depicting the religious figure’s name in Hebrew: Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, Sarah, Rebecca, Leah. I obviously can’t say if there are actual skeletons of those people underneath each banners, but this is the gravesite that a world of people have decided to believe in, and that’s pretty cool.

The entire chamber was almost entirely empty. Idan, who’d been there before, stepped away for a moment to help some praying scholars form a minyan (that is, a group of at least 10 Jewish adults needed to perform certain prayers) while I hung out solo. There were a couple of stone basins lit up with traditional memorial Jewish yarzeit candles, and I decided to light one for each of my deceased grandparents. A nice plan, except there were no matches to be found, and no Idan nearby to supply me with a lighter. So, not wanting to leave and disturb someone in the halls asking in terrible Hebrew for a light, I started to crawl around looking for a spare match. If I never expected to be in the tomb of my religion’s founders, then I can safely say I also didn’t expect to be slithering on the floor there, examining broken matches like a hobo. I finally found the remains of a matchbook, and then there was light. Kin, welcome to the tombs.

Photos by Alyssa Kurtzman

I found Idan outside the main chamber, and we left to explore the rest of Hebron. We went wandering up toward the Arabic neighborhoods on the hills above us, exploring a very old-looking cemetery as I took photos of some of the crumbling abandoned buildings (and one gutted 70’s-era Schwepps Truck) surrounding us. I stepped into the doorless atrium of one former home, empty except for a tipped-over desk chair. Idan stepped in behind me as I was snapping a picture and gasped. I turned nervously to him: “What?” “We used to smoke in here!” Ah, yes.

These vacant areas of the city really were like a patchy, cement playground. In parts where the hills were steep enough and the buildings close enough together, you could leap from rooftop to rooftop. (Try not to sing the Aladdin song. Try not to sing the Aladdin song.) Idan showed me different parts of the city where he had been stationed: tall guard towers, assorted little barred kiosks near schools and markets. Eventually, we had wandered high enough that I worried we were encroaching on the less outsider-friendly neighborhoods. “Oh, don’t worry,” said Idan, reassuring me that we had been in that section for some time now.

Along one road above us, two boys poked their heads out from behind a stack of burlap sacks. “Salaam!” they greeted us. “Salaam!” we said. Then, hesitantly, they said “Hello!!” “Hello!” we said back, still from a distance. The boys looked gleeful, probably that they had gotten us two idiots to mimic them. From behind the stacks emerged someone who looked like their father, investigating what his sons were yelling at. We exchanged waves, and then he shouted something down to us in Arabic that I didn’t understand. Idan turned to me. “He wants to know if we want to come up for some coffee.”

I can’t pretend that I wasn’t a little nervous to approach a strange Arabic man, wearing jeans and no head cover, accompanied by an Israeli male that I wasn’t married to, in the supposedly unfriendly section of a city in the mostly hotly contested territory in the world. But I knew to follow Idan’s experienced lead. Good thing we both love coffee.

We walked up to the gate of the man’s home, and he let us in. We followed him around the back of the small house, where children were playing in a little yard next to a wooden shed. When we walked through the doorway into the house, I half-expected to find a gathering of other tourists, similarly puzzled to have been invited in. Instead, we were led into a beautiful parlor with intricately upholstered furniture. The man invited us to sit, and we started chatting. His Hebrew was about as stilted as mine, which made it one of the most productive conversations I’ve ever had in that language. He told us he was a sandal-maker, and we told him we were visiting from Tel Aviv but I was originally from New York. The two sons came in with their sisters, sitting down and pointing at us, giggling to each other.

The man’s beaming wife came in with a tray of beautiful silver Arabic coffee cups. In case you haven’t had it, Arabic coffee is kind of like espresso but stronger, darker, and brewed with almost equal parts grounds and sugar—at least if you make it right. We all took a cup and then she sat down, too. At this point, the sons were bored enough to turn around and start playing some shoot ’em-up computer game with Arabic subtitles, but the girls stayed put. One of them started playing with the big SLR camera around my neck, and her mother shooed her away. “That’s alright!” I said. I showed her how to look through the viewfinder and how to twist the lens to zoom the picture in and out, and she was entranced.

An older woman came in and the man introduced her as his mother. The granddaughters jumped aside so she could sit, and she asked her son a question, which he relayed to us. Are we married? I don’t know the Hebrew or Arabic word for ‘platonic’ but I think leaning back and shaking your head with your eyes wide open is universal code. “No, no, no, we’re friends.” The women both started laughing at this absurd notion, and Idan and I just kind of smiled and shrugged. Then, the man asked us if we wanted to see his factory. (Actually, I don’t know for sure if he explicitly said “factory,” because Idan had to translate that one for me.) I still couldn’t believe where we were and how unremarkable it all seemed—not that it was a mundane experience, but that it was exactly what you might expect from a conversation over a coffee with some friendly people you don’t know.

After we finished the coffee, back outside we went. This time, we walked down into that little shed in the backyard—the sandal factory. Inside were four old men working at ancient-looking sewing machines and smoking cigarettes. Our host showed us a few finished products and told us that his sandals were some of the best quality you could find in the Israeli markets. Idan and I promised to tell our friends.

And that was it. Idan shook the man’s hand, we thanked him and his family for hosting us. I wish I had gotten a photo of all of us together, but regretfully I didn’t even think of it, not to mention my new little friend was having too much fun with the camera for me to want to take it back any earlier than necessary. We didn’t realize until later that Idan had been wearing his yarmulke that whole time.

The rest of the trip was entirely uneventful: We watched stray dogs and ate sandwiches from the gift shop while we waited for the bus back. When it came, we hopped on and headed back to Jerusalem.

I don’t know what groundbreaking lessons are to be grasped from our day in Hebron, except perhaps that 1. Religion is quite a powerful thing and 2. People are generally as generous as they are curious. That said, I can’t say that I would have traveled to such a foreign place without a trustworthy friend who knew the city so well. Before the trip, I never expected any experience in Hebron to top the Tombs in terms of enlightenment, but then I got a rare chance to see the expectation of culturally-rooted animosity completely disproved. Also, I can say that I have breathed the ground-dust of the holy tombs of the Matriarchs and Patriarchs, and it smelled like history.

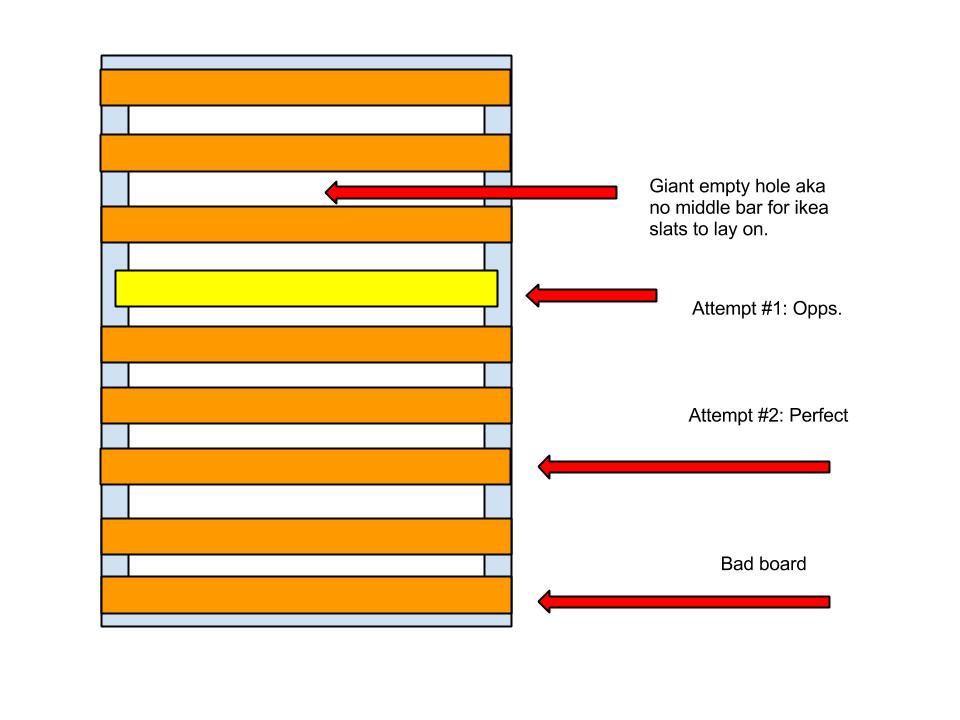

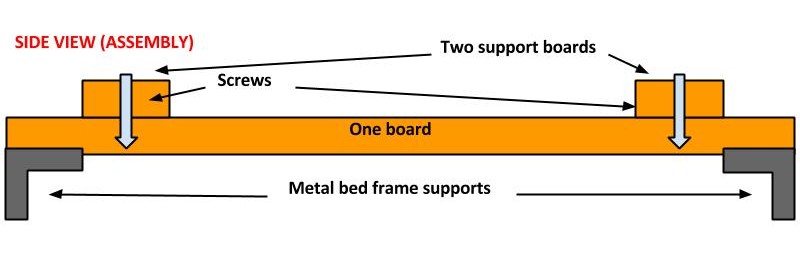

If only I had made these drawings BEFORE I started and not just for this article. Add that to the lessons-learned list.

If only I had made these drawings BEFORE I started and not just for this article. Add that to the lessons-learned list.