Working in a hardware store, I come into contact with a lot of do-it-yourself-ers. While I admire their efforts, often they need an expert, or at least someone with a little experience, to help point them in the right direction. One of the most common problems customers bring to my attention involves staining, both interior furniture and deck stains. It’s a lot harder to fix mistakes made while staining than it is if you mess up while you’re painting, and many people jump into a large project without doing their research. Here are some of the FAQs that are often brought to me by customers:

How do I prepare?

The most important part of any home improvement project is the preparation. You need to have the proper tools and know the proper techniques, or you’re going to have a bad time. When it comes to staining, this comes down to knowing what type of surface you’re working with, and whether it is new or old. I frequently have customers tell me they aren’t sure if their piece is even made of real wood, or whether it has been stained in the past. The answer I usually give is to try a little stain on a small, hidden area, and see what happens. If it soaks into the wood, you’re probably fine to stain the whole thing. If it doesn’t, stop trying, it’s not going to work. If the stain is just pooling up on top of the piece, it either is not able to be stained, or there is another coating or stain already on the wood that needs to be removed. In terms of equipment, you should have a brush, a rag to wipe off excess stain, and something to clean your brush (soap and water for water-based stain, and mineral spirits for oil-based). Unless your stain is designed to be wiped on, you should always use a brush. Exterior stains can be applied with a brush, roller, or sprayer, but check your product for recommendations before beginning.

What does a stain do?

Another misconception a lot of customers have is that a stain, like paint, is just an exterior coating. One of the most common problems my customers have is that they’ve tried to apply a stain as if it was a paint and, in many cases, directly over existing paint, or other coatings. Stain only works on bare wood, because it needs to soak into the wood fibers. Imagine your wood as a bundle of drinking straws. The straws can soak in water, and other liquids. However, there is a limit to how much the straws can absorb, and, of course, if they are blocked by something, they won’t soak in anything at all. Stain needs to soak into wood, and when it dries the fibers of the wood grain lock the color inside. A paint or clearcoat goes on top of the wood, and will prevent other liquids from soaking in, and make the piece more durable. You typically go over interior stains with polyurethane when you are done.

How can I stain something that has been painted or sealed?

The basic answer is: you can’t. You have to remove the paint in order to properly stain the wood. This is by far the most frustrating part of staining for customers unfamiliar with the process. Many decide to try anyway, only to return in a few hours even more frustrated. Defiant to the end, I’ve seen customers go through darker and darker stains, thinking a darker color would just cover up their mistakes, rather than taking my previous advice. In the end, their piece was ruined, and as far as I can tell they never attempted to remove anything they applied to it.

What about removing an old stain?

Unless you’re changing your stain color or switching to a water-based stain from an oil-based, you usually don’t have to remove your old stain at all. Just remember, a water-based stain can’t go over an oil-based stain. Removing stain is not particularly hard, but it will take patience. For interior stains, you have the option to sand the wood, or strip it. I usually recommend stripping, because it requires the least amount of grunt work. Sanding is cheaper, but harder, and you are more likely to damage your wood from over sanding. Most strippers just need to be brushed on, and let sit for a while, and then rinsed off. For interior stains this isn’t that hard at all, but for exterior deck stains, it’s a larger and more complicated task. Exterior stain remover usually comes in a concentrated form (so you can make a large quantity of it) and should be applied to the entire surface you want to remove the stain from. Unlike some strippers, these types of removers usually require their own neutralizer product. At this point is when most customers decide to just paint their deck instead–just saying.

With this information, your next staining project should be a breeze! The real key to staining, and any other household project for that matter, is to take the time to understand the process, and what types of stumbling blocks you might encounter. Staining is never a simple project to undertake, so consider whether it’s really worth your time. It can make your furniture and deck look fantastic, but only if done properly. If you’re looking for a quick-fix, try painting instead.

Photo by Rob Adams

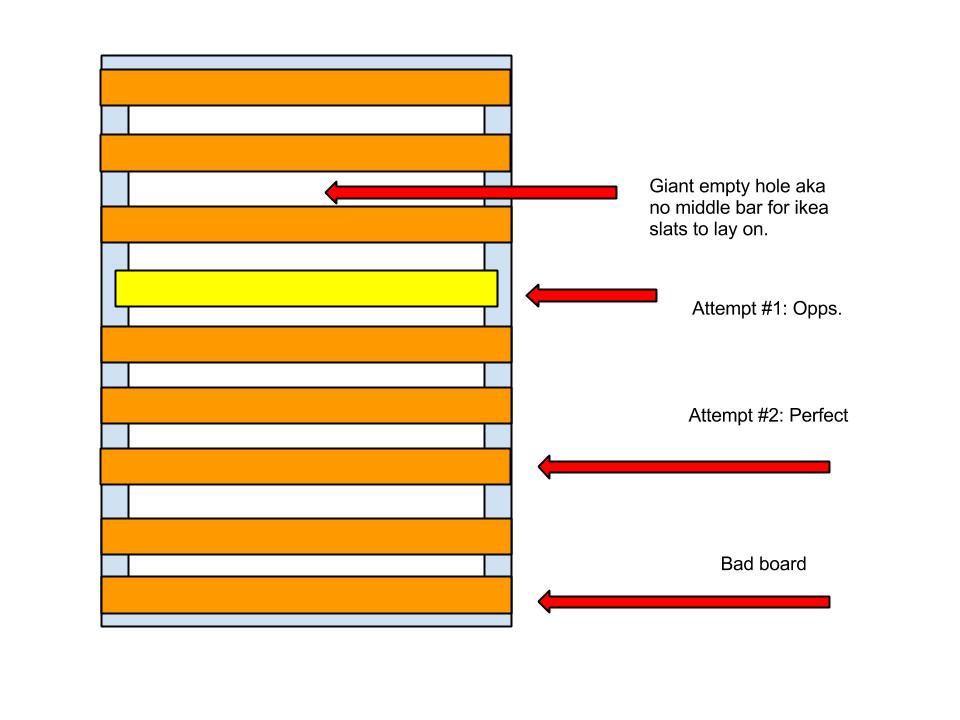

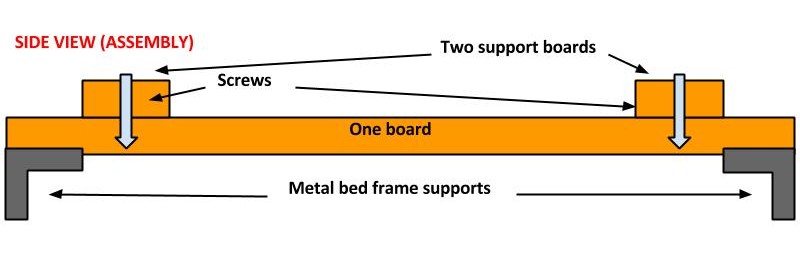

If only I had made these drawings BEFORE I started and not just for this article. Add that to the lessons-learned list.

If only I had made these drawings BEFORE I started and not just for this article. Add that to the lessons-learned list.