As a kid, I was blessed with a hyperactive imagination and a dramatic sense of destiny. These are both helpful once you’re older and trying to be assertive in your creativity… but if you’re at a stage in your life when you’re obligated to take an afternoon nap, it makes you a tiny lunatic. I believed in Santa until I was prepubescent (who cares what other people said, I had the logic worked out), and nobody could prove that dragons didn’t actually exist so I inverse-propertied that shit and stubbornly held out (we just haven’t been looking in the right places). This was just the more fantastical stuff—you can only imagine how I was about anything over which I actually thought I had control.

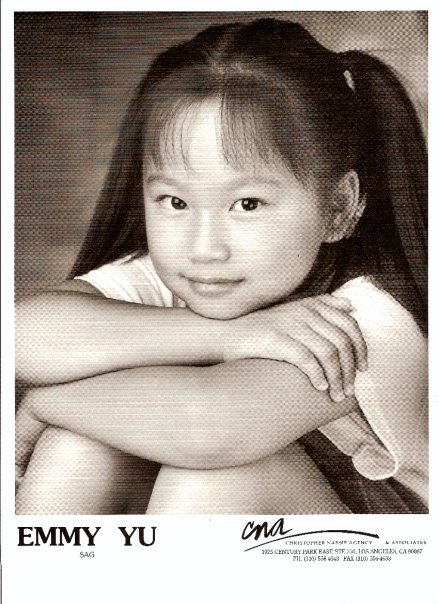

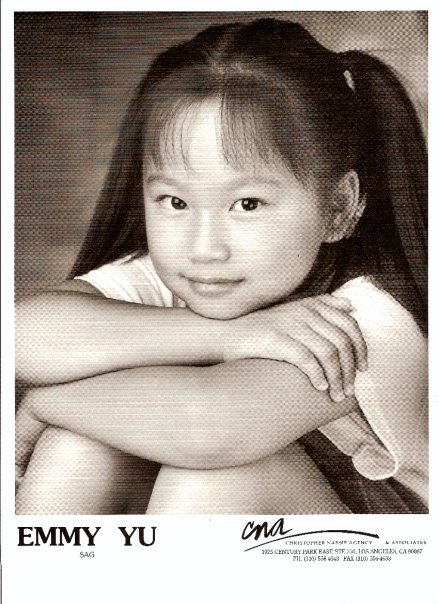

Photo Submitted by Emmy Yu

I started acting in films when I was 5. Ask me some other time, and I can go into the details of how bittersweetly intoxicating it was—the intricacies of how quickly and willingly any child ruled by wild, hungry imagination would slip under that wave of magical make-believe. For now though, let’s just suffice to say that set life was pretty sweet. There was free food always, someone announced my presence over walkie-talkie whenever I was anywhere, and working meant having my face on all the monitors. I fucking loooved it. (I’m a Capricorn. You know who else was a Capricorn? Stalin.) Point being, when I realized that this was something that I was getting paid to do and technically could get paid to do for the rest of my life and, therefore, not need to do anything else but this all the freaking time… well, I was in.

I turned 6. And chose what I (thought I) would do for the rest of my life.

It’s fascinating how attached you can become to even the most trivial choice. You embrace it because it gives definition to that messy, inscrutable concept of “self” you have in your mind. You lock it down in front of you so you can trace the shape of it with your eyes and claim that this is you. It’s incredibly satisfying… until, of course, it’s not. Heavy-hitters like Fight Club and Mad Men explore the “not” in a way that I can’t even attempt, but from my basic understanding of it, you either 1) start hating the shape you’re seeing or 2) someone (maybe everyone) starts telling you “Hey, you’re wrong. That’s not you at all.” And you’re expected to just let go.

The second was what happened to me and, honestly, it became clear pretty early on that I would not have a future in acting. But this was the choice I had made—not a trivial one in the slightest—and I was so very deeply attached. I closed my eyes to the (mostly well-intentioned, for the record) Dead End Ahead messages I was getting.

I turned 10, I turned 11, I turned 12.

It’s difficult for me to step into this next part. Even with the time I’ve had to soften the light and mute the volume, I try not to dwell on the memories of this time because it’s so easy to linger and ask unheard, unanswerable questions. To keep it brief, the auditions were torture. The stifling hush of cattle-call waiting rooms, where I spent at least 45 minutes for every 5 I actually auditioned. The canned “thank you” responses that I carefully memorized, word for word, so later I could pick them apart, turn them over in my fingers and see if they meant something else. The dwindling callbacks. The incredible silence from the phone—undeniably the most judgmental silence I have ever experienced.

I turned 17.

I don’t believe that I was an unusually intense child; it was just an atypical context for someone of that age to find herself in. So, with the logic of my years, I decided that this whole experience couldn’t simply be something that was just happening to me—it had to be as melodramatic as “destiny.” How on earth could anyone expect me to let go? It had been molded into my identity for as long as I could remember and, no, it wasn’t even a significant time investment out of my year anymore—much less my day to day—but it was part of me. You may as well have asked me to hack my arms off.

I can make jokes about it now (armless kids are funny, guys) but really, I struggled with it. So I gave myself a cheat and went off to film school that fall to study writing and directing. I packed your usuals—you know: clothes, new laptop, headshots, kitchenware. I gave myself a little hope. I wasn’t letting go of acting entirely—I would just come back to it later, and everything I had ever known about myself would still be true. Everything I had ever insisted to be true would be true.

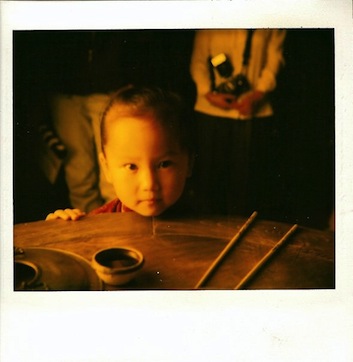

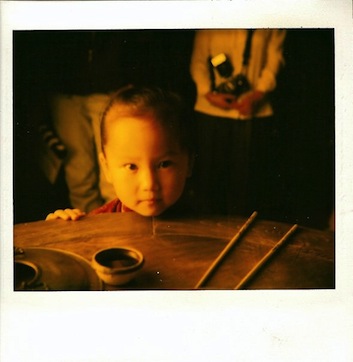

Photo Submitted by Emmy Yu

There’s no dramatic, climactic ending to this story. There was no eureka! moment when I suddenly said, “Hey, get over it,” and then I did. College and post-grad life led to a natural diminishment in the time and energy I put into keeping acting on my mind. Admittedly, at the time, this was a transition I ignored because it was too painful to accept. Better to cover it up with dismissive jokes about “my acting days of yore.” Even now, I find myself fighting my panicked instinct to minimize the significance—to look it in the eye, this darling, childish fantasy of mine, and say that acting was just a phase I went through. But I’ve also wised up to the fact that this is a kind of denial—the emotional equivalent of smiling after you’ve knocked your own teeth out.

Somewhere between ages 5 and 18, I missed the memo that there is always a gap between who you are and who you want to be, and sometimes that gap is unbridgeable. Acknowledging reality—that this thing I once thought was an everlasting part of my life would actually end up as a montage in my head—was a terribly painful but necessary step in growing up. And I’m not even sure how it happened but I can say that it did. I stopped paying my SAG/AFTRA dues. I don’t even remember where my headshots are stored.

The concept of “letting go” is a horrible, shrieking abomination—one of life’s unfortunate staples that will hold you down beneath the surface of all your expectations, breathless, drowning in your impotence. What’s worse is that your instinct to fight it will cause you just as much pain—the lengths to which you will go so you can trick and manipulate yourself into thinking that it’s done or that it didn’t matter. If you find yourself there, be honest with yourself but be gentle, too. Be okay with the fact that you had hoped for something you couldn’t control and it ultimately disappointed you. Paolo Coelho said “Everything will be okay in the end. If it’s not okay, then it’s not the end.” The end comes when you least expect it and will be much easier than you ever imagined. You won’t even feel relief because you will have already floated on.

And if that’s too flowery to digest, just think of it as forcing yourself to throw up after a night of hard drinking.